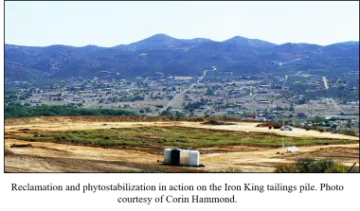

In Dewey-Humboldt, a small mining town just south of Prescott, Arizona, the abandoned Iron King Mine has long commanded the view to the southwest. During the dust storms that frequent the semi-arid desert, wind sweeps by, scouring the tailings pile and depositing particulates downwind, toward town. And when it rains, water pools on the abandoned tailings pile, picking up heavy metals before flowing off the mine site. The tailings pile itself, devoid of plant life, was a veritable moonscape—the substrate too acidic, too toxic, for anything to grow. Or it was until six years ago when researchers from the UA's Center for Environmentally Sustainable Mining (CESM) began exploring phytostabilization as a method for remediating the site and protecting the nearby communities.

Research being conducted at the Iron King site exemplifies the unique, innovative, and collaborative approach of the CESM. Through the center, researchers from the UA work hand-in-hand with industry mining partners to develop and implement cutting-edge, economical remediation models for both modern and legacy mine sites.

While pairing the words "sustainable" and "mining" might arouse suspicion in some, the approach follows a logical guiding principle:

"The CESM is trying to bring together industry with innovative technologies developed in academia so we can make environmental stewardship of these sites better and more affordable," said Dr. Raina Maier, Director of the CESM and principal investigator of the Iron King Project.

Arizona's mining industry contributed approximately $4.8 billion in income to Arizona workers, business owners, and local governments in 2011, and provided an estimated 52,100 jobs to Arizona residents. This, paired with the fact that Arizona is home to one of the largest undeveloped copper resources in the world, make regulation and reclamation essential.

"Mining is huge in the Southwest," said Dr. Jon Chorover, co-investigator on the Iron King Project. It's a big part of Arizona's economy and a growing part of global commerce. How do we mine in a way that minimizes the negative environmental consequences?"

The majority of research regarding public health impacts of mining has focused on contamination of water supplies, so there is relatively little known about the health effects of inhaling airborne mining particulates.

"Our modern sites do a good job of extracting out all the metals, but in order to do that they grind the rock finer and finer, so the problem is they're generating particulate sizes that are regulated as air pollution by the EPA," Maier said.

Mining companies know this; they're tasked with reclaiming mining sites, but the technology for effectively and efficiently doing so has been slow to evolve. The current method of reclamation involves capping the tailings pile with between six inches and three feet of soil, rock, and or gravel. They cap the pile, then hydroseed it and walk away. According to Maier, very little has been published about this method, and it is both water-intensive and costly.

"If you have a 1000-acre site and you have to cover it in six •nches to three feet, that's a lot of material, and where does it come from? Often, the pristine desert next door, which creates a whole new problem," said Maier.

Scientists from the CESM set out to determine whether the cap was really necessary, or if another sort of amendment, mixed directly with the tailings, could promote plant life and an equally stabilizing cover for less money. Phytostabilization— mproving the tailings piles with compost and other amendments and then planting and supporting the growth of native plants—seeks to secure the contaminants in the plants' root zone rather than allowing them to be drawn up into the plant tissue where they become available to foragers.

"Though Iron King is a particularly nasty example of mining impacts, tests successful at that site are likely to work very well on less heavily-impacted sites," Maier said.

Upon hearing about the innovative phytostabilization research, three mining companies invited Maier and other scientists from the CESM to study their sites. They partnered by supporting the research at a rate of 50 percent for the first two years, and paying the entire bill thereafter. Through the CESM, Maier used TRIF funds to seed this Industry-University Cooperative for site-specific research at the mines, with an additional perk that the mines agree to publicly share the research results from their sites.

"It's helpful to the mining companies because they're required to document to the land owner that they're reclaiming and show that their reclamation is working," Maier said. "They're extremely interested because we're developing easily measurable indicators of success and failure."

Innovative approaches to mining reclamation aren't all that the CESM funds: their interdisciplinary program supports more than 70 people from multiple colleges working on five different research projects. Staff, students, and faculty from the colleges of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, Agriculture and Life Sciences, Engineering, and Public Health all come together for research on biomedical and environmental science projects related to mining.

CESM In Action

Gardenroots:

For her PhD research at the UA, now-faculty member Dr. Monica Ramirez-Andreotta worked with communities near Dewey-Humboldt to research metal uptake in plants. She helped local residents make informed decisions about what crops could be most safely grown in home gardens near the Iron King site. Now called "Arizona Gardenroots", Ramirez-Andreotta has expanded the program to conduct similar studies and promote public health and garden knowledge throughout the state.

Tribal College Mining Educational Modules:

Drs. Karletta Chief and Maier along with other UA scientists partnered with Tohono O'odham Community College to develop educational modules about the processes, environmental impacts, reclamation and socio-cultural impacts of copper mining. The tribal college modules offer instructors materials and hands-on activities that are stand-alone and can be easily incorporated into the existing curriculum to help tribal college students better (Photo courtesy OfKarletta Chief) understand mining-related challenges. The goal is to empower young Native students to pursue an education in environmentally-related degrees and then return to build the capacity of their tribes. "We're trying to get the students to understand the issues and connect what they're doing in school to something that's really important to their tribe," said Chief.

Phytostabilization:

At Iron King, Chorover and PhD candidate Corin Hammond knew that phytostabilization cut down on wind erosion and surface runoff of toxic tailings, but they wanted to know what exactly was happening underground. They investigated how plants responded to contaminants like arsenic and lead, both of which are found in high concentrations at the Iron King Mine. One exciting finding is linked to the native mesquite root: mesquite trees seem to store arsenic in crusts around their root—an encouraging prospect for future remediation approaches.

"We're getting ready to publish exciting results which indicate that, although we were concerned that the addition of organic matter and water could mobilize some of the contaminants, we see that in fact it promotes weathering and biological activity," Chorover said. "Weathering is not making these elements more mobile, instead it is transforming them into more thermodynamically stable forms of the contaminants that are then retained in the root zone."